Driving into the future by illuminating the past.

Dividing Lines is a tour of the history of residential segregation and its far-reaching impacts.

Residential segregation and the racial wealth gap didn’t just happen through some automatic human instinct or by chance. Individual actions in tandem with state and federal policies created our current reality.

By highlighting the history of segregation in Kansas City, Dividing Lines sheds light on the governmental policies and individual actions which decimated Black neighborhoods all over the United States. This experience will expand the tour by comparing the history of Kansas City to that of St. Louis, Indianapolis, and Birmingham.

You can also experience Dividing Lines in the real world. For more information, visit the driving tour site.

The content of this tour may contain controversial material; such statements are not an expression of library policy.

How this tour works

The Dividing Lines virtual tour is embedded in this page in three 30-minute videos. Each video is like a chapter in a book. Before and after each video, additional content expands the story to the national context.

360°

Experience

The tour allows you to immerse yourself in a unique 360° virtual environment.

A Front

Street View

On this tour, you will see many historic landmarks and interactive panoramas from all over Kansas City.

The History

of Kansas City

While this tour focuses on Kansas City’s history, the policies and practices discussed were present across the country.

Chapter 1: Since When is “Restricted” a Good Thing?

With the support of Federal Housing Policies, developers leaned heavily on racially restrictive covenants to ensure that their newly-built neighborhoods remained segregated.

Restrictive Covenants Here, Racial Zoning There

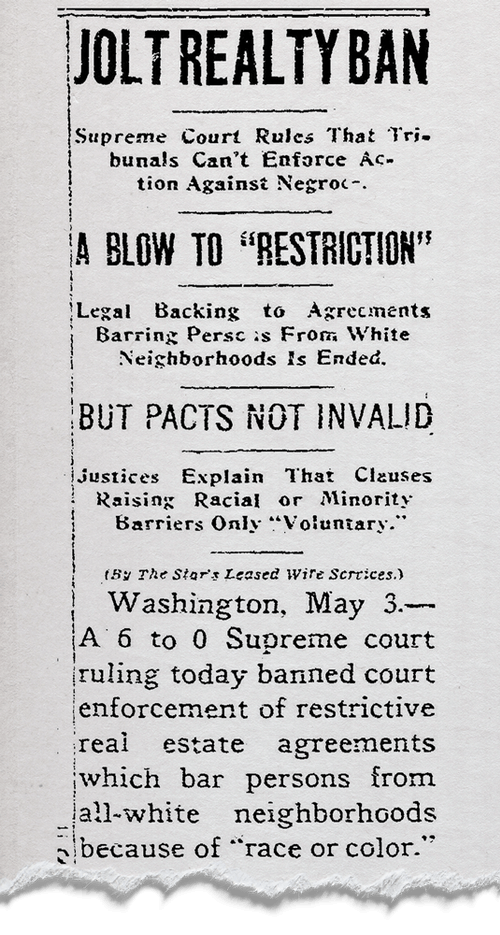

During the twentieth century, racially-restrictive deeds and covenants became a prevalent part of real estate and homeownership in the United States. Covenants were included in home deeds throughout the country to prevent most members of minority groups from purchasing or even occupying a particular property.

The Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that these restrictive covenants could no longer be enforced in court as it would violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. However, private parties could continue to abide by and enforce such terms of restrictive covenants. The Fair Housing Act, passed in 1968, finally made it illegal to discriminate in the sale or rental of housing on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, familial status, and disability.

Chapter 2: “Planning for Permanence” for Whom?

While white people were lured away from city centers to the gleaming suburbs, official federal policy allowed banks to deny Black people access to the affordable credit they needed to own and improve their homes.

So Far, So Permanent

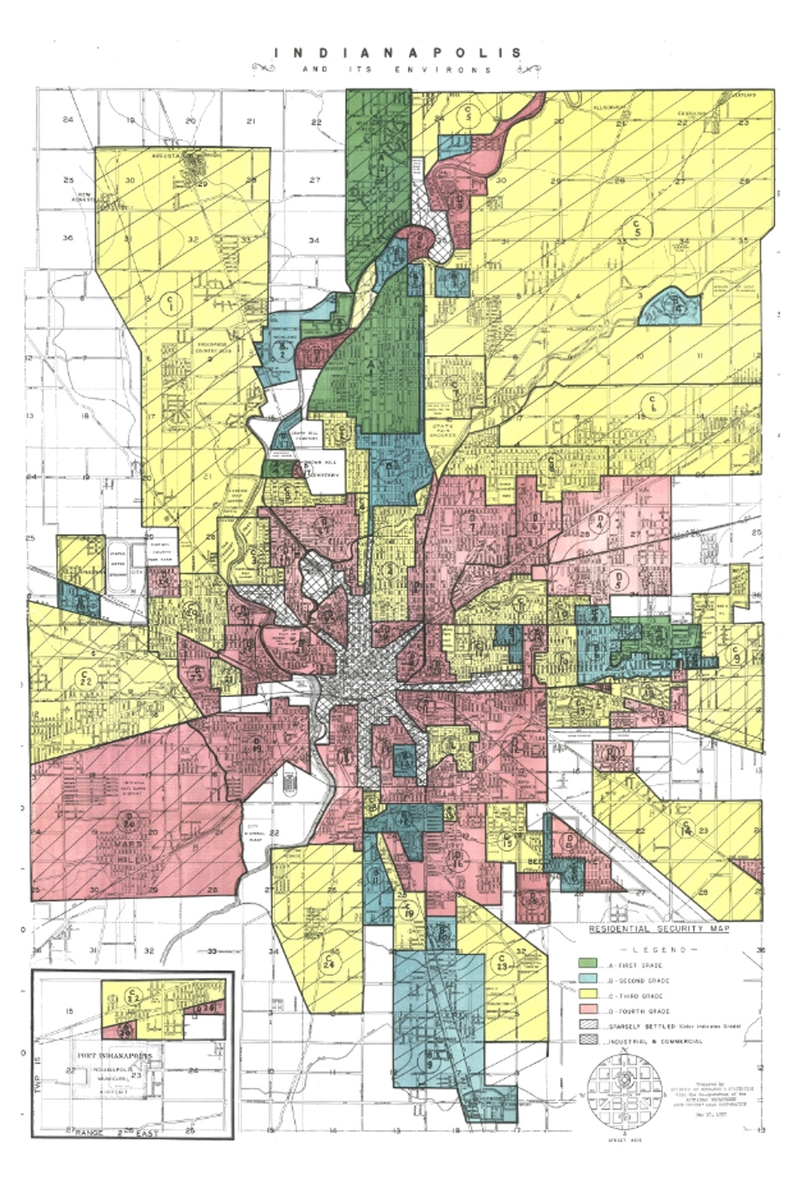

Residential security maps were created by the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) - a precursor to the Federal Housing Authority or FHA. In the late 1930s, the HOLC placed neighborhoods into four categories: best, still desirable, definitely declining, and hazardous. These categorizations were based primarily on the racial makeup of the neighborhood. Neighborhoods with minority occupants were marked in red and were considered the highest-risk for mortgage lenders. The Mapping Inequality Project allows you to view residential security maps for cities across the country.

Featured in this section is a residential security map for Indianapolis. To this day, the Butler-Tarkington neighborhood (the large green triangle near the top of the map) is almost exclusively home to white residents.

Chapter 3: Two Types of Progress

Even while policies continue to disadvantage Black neighborhoods, the Black community and allies of all races still struggle for the right of Black people to thrive in the face of this long violent history.

Progress in Spite of Official Policy

In the latter half of the 20th century, public works projects were completed across the country. These projects presumably signaled the gleaming future that lay ahead for our cities. Many of these projects were intentionally meant to displace or further separate the places where Black communities had been forced into by official policy. Many people considered this to be beneficial "slum clearance," with the Kansas City Star running headlines such as, “Dream a City Without Slums” (December 19, 1952, D-4) or “Slum War is On” (July 3, 1955, 7E).

On the other hand, alongside the history of disinvestment and racist policy there have always been people fighting for justice and equity. These concurrent efforts must not be forgotten or overlooked. While Alan and Yolanda Young were reinvesting in their community in Kansas City's Ivanhoe neighborhood, in Birmingham, people in the Titusville neighborhood were similarly working to strengthen and maintain the neighborhood for current residents in the face of gentrification.

Photo by David M. Rainey (@PhotoRainey)

Moving Forward

Dividing Lines is meant to help you understand how we got here. Our neighborhoods and school and workplaces aren’t the way they are by accident. Hopefully, it shone a light on how individual actions contribute to systemic issues. You have power to make real and incremental changes - learn more through the following resources:

About this tour

The Dividing Lines tour was originally developed from ideas by Erik Stafford and Paul Richardson for students participating in the Race Project KC program. Thank you to our interviewees Davionne Cannon, Lauren Cole, Mamie Hughes, Margaret May, Mia Rios, Bill Tammeus, and Sid Willens.

Video production for the virtual tour provided by Brainroot and web design provided by Kalimizzou.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does the tour look blurry on my device?

360 video represents a whole lot of data streaming to your device. If your connection speed is slow or your data is metered, YouTube may automatically ramp down the resolution on the virtual tour. If you have access to higher data speeds through wifi, we recommend manually setting the resolution (lower right corner of the video frame) to at least 1440s.

I’m viewing the tour using a VR headset and am feeling dizzy. Is this normal?

Some people do experience discomfort when using a VR headset. Likewise, the eyes can take a moment to adjust to the real world after you have been using a headset for a prolonged period of time. Although this discomfort is not unexpected, we recommend sitting down and taking a break before continuing if you are experiencing these symptoms.

I’d like to take the driving tour rather than the virtual tour. Where can I find it and how do I do it?

The Dividing Lines driving tour is hosted on the Voicemap app. To take the tour, download the Voicemap tour on your mobile device. Click on “Kansas City” once you have successfully downloaded the app. Navigate to the Dividing Lines tour and download it. Drive to the north parking lot of Shawnee Mission East High School (7500 Mission Rd, Prairie Village, KS 66208) to begin the tour.